Why Did Art Spiegalman Go to a Mental Hosepital

| Fine art Spiegelman | |

|---|---|

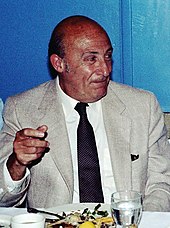

Art Spiegelman in 2007 | |

| Born | Itzhak Avraham ben Zeev Spiegelman[1] (1948-02-15) February xv, 1948 Stockholm, Sweden |

| Nationality | American |

| Surface area(due south) | Cartoonist, Editor |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse(s) | Françoise Mouly (m. 1977) |

| Children | ii, including Nadja Spiegelman |

Art Spiegelman (; born Itzhak Avraham ben Zeev Spiegelman on February xv, 1948) is an American cartoonist, editor, and comics advocate best known for his graphic novel Maus. His piece of work as co-editor on the comics magazines Arcade and Raw has been influential, and from 1992 he spent a decade every bit contributing artist for The New Yorker. He is married to designer and editor Françoise Mouly, and is the father of writer Nadja Spiegelman.

Spiegelman began his career with Topps (a bubblegum and trading card company) in the mid-1960s, which was his main financial support for ii decades; there he co-created parodic series such equally Wacky Packages in the 1960s and Garbage Pail Kids in the 1980s. He gained prominence in the underground comix scene in the 1970s with curt, experimental, and often autobiographical work. A selection of these strips appeared in the collection Breakdowns in 1977, after which Spiegelman turned focus to the volume-length Maus, virtually his relationship with his male parent, a Holocaust survivor. The postmodern volume depicts Germans as cats, Jews as mice, and ethnic Poles every bit pigs, and took 13 years to create until its completion in 1991. It won a special Pulitzer Prize in 1992 and has gained a reputation as a pivotal work.

Spiegelman and Mouly edited eleven issues of Raw from 1980 to 1991. The oversized comics and graphics magazine helped introduce talents who became prominent in alternative comics, such as Charles Burns, Chris Ware, and Ben Katchor, and introduced several foreign cartoonists to the English-speaking comics world. Beginning in the 1990s, the couple worked for The New Yorker, which Spiegelman left to work on In the Shadow of No Towers (2004), about his reaction to the September 11 attacks in New York in 2001.

Spiegelman advocates for greater comics literacy. As an editor, a teacher at the School of Visual Arts in New York City, and a lecturer, Spiegelman has promoted better understanding of comics and has mentored younger cartoonists.

Family history [edit]

Spiegelman's parents were Polish Jews Władysław (1906–1982) and Andzia (1912–1968) Spiegelman. His begetter was born Zeev Spiegelman, with the Hebrew proper noun Zeev ben Avraham. Władysław was his Polish proper noun, and Władek (or Vladek in anglicized form) was a atomic of this proper name. He was also known as Wilhelm under the German occupation, and Anglicized his proper name to William upon immigration to the U.s.. His female parent was born Andzia Zylberberg, with the Hebrew proper name Hannah. She changed her proper noun to Anna upon immigrating to the U.s.a.. In Spiegelman'due south Maus, from which the couple are all-time known, Spiegelman used the spellings "Vladek" and "Anja", which he believed would be easier for Americans to pronounce.[iii] The surname Spiegelman is High german for "mirror man".[4]

In 1937, the Spiegelmans had one other son, Rysio (spelled "Richieu" in Maus), who died before Art was built-in,[i] at the historic period of five or six.[5] During the Holocaust, Spiegelman's parents sent Rysio to stay with an aunt with whom they believed he would be safe. In 1943, the aunt poisoned herself, along with Rysio and two other young family members in her intendance, and then that the Nazis could not take them to the extermination camps. After the war, the Spiegelmans, unable to accept that Rysio was expressionless, searched orphanages all over Europe in the hope of finding him. Spiegelman talked of having a sort of sibling rivalry with his "ghost brother"; he felt unable to compete with an "ideal" brother who "never threw tantrums or got in whatever kind of trouble".[6] Of 85 Spiegelman relatives alive at the offset of World War Ii, but xiii are known to have survived the Holocaust.[vii]

Life and career [edit]

Early life [edit]

Spiegelman was built-in Itzhak Avraham ben Zeev[one] in Stockholm, Sweden, on February 15, 1948. He immigrated with his parents to the United states of america in 1951.[8] Upon immigration his proper name was registered as Arthur Isadore, just he later had his given name changed to Art.[ane] Initially the family settled in Norristown, Pennsylvania, and so relocated to Rego Park, Queens, New York City, in 1957.

He began cartooning in 1960[8] and imitated the fashion of his favorite comic books, such as Mad.[9] In the early 1960s, he contributed to early fanzines such equally Smudge and Skip Williamson's Squire, and in 1962[x]—while at Russell Sage Junior High School, where he was an honors educatee—he produced the Mad-inspired fanzine Blasé. He was earning money from his drawing past the time he reached high school and sold artwork to the original Long Island Press and other outlets. His talent caught the eyes of United Features Syndicate, who offered him the adventure to produce a syndicated comic strip. Defended to the thought of art as expression, he turned downwards this commercial opportunity.[9] He attended the Loftier School of Fine art and Design in Manhattan beginning in 1963. He met Woody Gelman, the fine art director of Topps Chewing Gum Visitor, who encouraged Spiegelman to apply to Topps after graduating from high school.[8] At age fifteen, Spiegelman received payment for his work from a Rego Park newspaper.[11]

Subsequently he graduated in 1965, Spiegelman's parents urged him to pursue the financial security of a career such every bit dentistry, but he chose instead to enroll at Harpur College to study art and philosophy. While there, he got a freelance fine art job at Topps, which provided him with an income for the side by side ii decades.[12]

Spiegelman attended Harpur Higher from 1965 until 1968, where he worked every bit staff cartoonist for the higher newspaper and edited a college humor magazine.[13] After a summertime internship when he was 18, Topps hired him for Gelman'southward Product Evolution Department[fourteen] equally a creative consultant making trading cards and related products in 1966, such as the Wacky Packages series of parodic trading cards begun in 1967.[xv]

Spiegelman began selling self-published underground comix on street corners in 1966. He had cartoons published in underground publications such equally the Due east Hamlet Other and traveled to San Francisco for a few months in 1967, where the underground comix scene was just beginning to burgeon.[15]

In belatedly wintertime 1968, Spiegelman suffered a brief but intense nervous breakdown,[sixteen] which cut short his academy studies.[15] He has said that at the time he was taking LSD with corking frequency.[16] He spent a month in Binghamton State Mental Hospital, and shortly after he exited it, his mother died past suicide post-obit the expiry of her only surviving brother.[17]

Underground comix (1971–1977) [edit]

In 1971, after several visits, Spiegelman moved to San Francisco[15] and became a part of the countercultural underground comix motion that had been developing there. Some of the comix he produced during this period include The Compleat Mr. Infinity (1970), a 10-page booklet of explicit comic strips, and The Viper Vicar of Vice, Villainy and Vickedness (1972),[18] a transgressive work in the vein of fellow underground cartoonist S. Clay Wilson.[xix] Spiegelman's work also appeared in underground magazines such as Gothic Blimp Works, Bijou Funnies, Immature Lust,[fifteen] Existent Pulp, and Bizarre Sex,[20] and were in a multifariousness of styles and genres as Spiegelman sought his artistic voice.[19] He also did a number of cartoons for men's magazines such as Condescending, The Dude, and Gent.[15]

In 1972, Justin Dark-green asked Spiegelman to do a three-page strip for the beginning event of Funny Aminals [sic].[21] He wanted to do ane about racism, and at first considered a story[22] with African-Americans as mice and cats taking on the role of the Ku Klux Klan.[23] Instead, he turned to the Holocaust that his parents had survived. He titled the strip "Maus" and depicted the Jews every bit mice persecuted by die Katzen, which were Nazis every bit cats. The narrator related the story to a mouse named "Mickey".[21] With this story Spiegelman felt he had constitute his voice.[11]

Seeing Green's revealingly autobiographical Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary while in-progress in 1971 inspired Spiegelman to produce "Prisoner on the Hell Planet", an expressionistic work that dealt with his mother's suicide; it appeared in 1973[24] [25] in Brusque Society Comix #1,[26] which he edited.[15] Spiegelman'south work thereafter went through a phase of increasing formal experimentation;[27] the Apex Treasury of Underground Comics in 1974 quotes him: "As an art class the comic strip is barely in its infancy. And so am I. Perhaps we'll grow upwardly together."[28] The often-reprinted[29] "Ace Pigsty, Midget Detective" of 1974 was a Cubist-style nonlinear parody of hardboiled criminal offence fiction total of non sequiturs.[xxx] "A Solar day at the Circuits" of 1975 is a recursive single-folio strip about alcoholism and low in which the reader follows the graphic symbol through multiple never-catastrophe pathways.[31] "Nervous Rex: The Malpractice Suite" of 1976 is fabricated up of cutting-out panels from the soap-opera comic strip King Morgan, M.D. refashioned in such a manner as to defy coherence.[27]

In 1973, Spiegelman edited a pornographic and psychedelic volume of quotations and dedicated information technology to his mother. Co-edited with Bob Schneider, it was chosen Whole Grains: A Volume of Quotations.[32] In 1974–1975, he taught a studio cartooning class at the San Francisco Academy of Art.[eighteen]

By the mid-1970s, the underground comix move was encountering a slowdown. To give cartoonists a safe berth, Spiegelman co-edited the anthology Arcade with Pecker Griffith, in 1975 and 1976. Arcade was printed by The Print Mint and lasted vii issues, 5 of which had covers past Robert Nibble. It stood out from like publications by having an editorial program, in which Spiegelman and Griffith endeavour to show how comics connect to the broader realms of artistic and literary culture. Spiegelman's own work in Arcade tended to be brusk and concerned with formal experimentation.[33] Arcade also introduced fine art from ages past, too as gimmicky literary pieces past writers such as William S. Burroughs and Charles Bukowski.[34] In 1975, Spiegelman moved back to New York Metropolis,[35] which put most of the editorial work for Arcade on the shoulders of Griffith and his cartoonist wife, Diane Noomin. This, combined with distribution problems and retailer indifference, led to the magazine's 1976 demise. Spiegelman swore he would never edit some other mag.[36]

Françoise Mouly, an architectural student on a hiatus from her studies at the Beaux-Arts in Paris, arrived in New York in 1974. While looking for comics from which to practice reading English, she came across Arcade. Avant-garde filmmaker friend Ken Jacobs introduced Mouly and Spiegelman, when Spiegelman was visiting, simply they did not immediately develop a mutual interest. Spiegelman moved back to New York after in the year. Occasionally the 2 ran across each other. After she read "Prisoner on the Hell Planet" Mouly felt the urge to contact him. An 8-hour phone call led to a deepening of their human relationship. Spiegelman followed her to France when she had to return to fulfill obligations in her architecture grade.[37]

Spiegelman introduced Mouly to the world of comics and helped her find piece of work equally a colorist for Marvel Comics.[38] Subsequently returning to the U.S. in 1977, Mouly ran into visa problems, which the couple solved by getting married.[39] The couple began to make yearly trips to Europe to explore the comics scene, and brought back European comics to show to their circle of friends.[40] Mouly assisted in putting together the lavish, oversized collection of Spiegelman's experimental strips Breakdowns in 1977.[41]

Raw and Maus (1978–1991) [edit]

Breakdowns suffered poor distribution and sales, and 30% of the print run was unusable due to printing errors, an experience that motivated Mouly to proceeds control over the printing process.[41] She took courses in offset press and bought a printing press for her loft,[42] on which she was to impress parts of[43] a new mag she insisted on launching with Spiegelman.[44] With Mouly as publisher, Spiegelman and Mouly co-edited Raw starting in July 1980.[45] The first issue was subtitled "The Graphix Mag of Postponed Suicides".[44] While it included piece of work from such established underground cartoonists as Crumb and Griffith,[36] Raw focused on publishing artists who were nigh unknown, avant-garde cartoonists such as Charles Burns, Lynda Barry, Chris Ware, Ben Katchor, and Gary Panter, and introduced English-speaking audiences to translations of foreign works by José Muñoz, Chéri Samba, Joost Swarte, Yoshiharu Tsuge,[27] Jacques Tardi, and others.[44]

With the intention of creating a volume-length work based on his father's recollections of the Holocaust[46] Spiegelman began to interview his father again in 1978[47] and fabricated a research visit in 1979 to the Auschwitz concentration camp, where his parents had been imprisoned by the Nazis.[48] The volume, Maus, appeared one chapter at a time equally an insert in Raw beginning with the second consequence in December 1980.[49] Spiegelman's father did not live to see its completion; he died on 18 August 1982.[35] Spiegelman learned in 1985 that Steven Spielberg was producing an blithe film about Jewish mice who escape persecution in Eastern Europe past fleeing to the Us. Spiegelman was certain the film, An American Tail (1986), was inspired by Maus and became eager to take his unfinished book come out before the movie to avoid comparisons.[l] He struggled to find a publisher[7] until in 1986, after the publication in The New York Times of a rave review of the work-in-progress, Pantheon agreed to release a collection of the start half dozen chapters. The book was titled Maus: A Survivor's Tale and subtitled My Father Bleeds History.[51] The volume institute a large audience, in role because information technology was sold in bookstores rather than in direct-market place comic shops, which by the 1980s had get the dominant outlet for comic books.[52]

Spiegelman began teaching at the School of Visual Arts in New York in 1978, and connected until 1987,[35] pedagogy aslope his heroes Harvey Kurtzman and Will Eisner.[53] "Commix: An Idiosyncratic Historical and Artful Overview", a Spiegelman essay, was published in Print.[54] Another Spiegelman essay, "High Art Lowdown", was published in Artforum in 1990, critiquing the High/Depression exhibition at the Museum of Modernistic Art.[54]

In the wake of the success of the Cabbage Patch Kids series of dolls, Spiegelman created the parodic trading carte series Garbage Pail Kids for Topps in 1985. Like to the Wacky Packages serial, the gross-out gene of the cards was controversial with parent groups, and its popularity started a gross-out fad among children.[55] Spiegelman called Topps his "Medici" for the autonomy and financial freedom working for the visitor had given him. The relationship was nevertheless strained over issues of credit and ownership of the original artwork. In 1989 Topps auctioned off pieces of art Spiegelman had created rather than returning them to him, and Spiegelman broke the relation.[56]

In 1991, Raw Vol. ii, No. 3 was published; information technology was to exist the last consequence.[54] The closing affiliate of Maus appeared not in Raw [49] but in the second volume of the graphic novel, which appeared later that year with the subtitle And Here My Troubles Began.[54] Maus attracted an unprecedented amount of critical attention for a work of comics, including an exhibition at New York's Museum of Modernistic Art[57] and a special Pulitzer Prize in 1992.[58]

The New Yorker (1992–2001) [edit]

![]()

Spiegelman and Mouly began working for The New Yorker in the early on 1990s.

Hired by Tina Chocolate-brown[59] as a contributing creative person in 1992, Spiegelman worked for The New Yorker for x years. His showtime comprehend appeared on the February xv, 1993, Valentine's Twenty-four hour period issue and showed a black W Indian adult female and a Hasidic man kissing. The cover caused turmoil at The New Yorker offices. Spiegelman intended it to reference the Crown Heights riot of 1991 in which racial tensions led to the murder of a Jewish yeshiva educatee.[60] Twenty-1 New Yorker covers by Spiegelman were published,[61] and he as well submitted some which were rejected for being too outrageous.[62]

Inside The New Yorker 'due south pages, Spiegelman contributed strips such as a collaboration, "In the Dumps", with children's illustrator Maurice Sendak[63] [64] and an obituary to Charles M. Schulz, "Abstruse Thought is a Warm Puppy".[65] Another of Spiegelman's essays, "Forms Stretched to their Limits", in an issue was almost Jack Cole, the creator of Plastic Man. It formed the basis for a book most Cole, Jack Cole and Plastic Human: Forms Stretched to their Limits (2001).[65]

The same year, Voyager Visitor published The Complete Maus, a CD-ROM version of Maus with extensive supplementary material, and Spiegelman illustrated a 1923 poem by Joseph Moncure March called The Wild Political party.[66] Spiegelman contributed the essay "Getting in Touch With My Inner Racist" in the September one, 1997, issue of Female parent Jones.[66]

Editorial cartoonist Ted Rall begrudged Spiegelman'south influence in New York cartooning circles.

Spiegelman's influence and connections in New York cartooning circles drew the ire of political cartoonist Ted Rall in 1999.[67] In "The King of Comix", an article in The Village Voice,[68] Rall defendant Spiegelman of the ability to "make or break" a cartoonist's career in New York, while denigrating Spiegelman as "a guy with one slap-up book in him".[67] Cartoonist Danny Hellman responded by sending a forged email under Rall'due south name to 30 professionals; the prank escalated until Rall launched a defamation suit against Hellman for $i.5 meg. Hellman published a "Legal Action Comics" benefit book to cover his legal costs, to which Spiegelman contributed a back-cover cartoon in which he relieves himself on a Rall-shaped urinal.[68]

In 1997, Spiegelman had his get-go children's volume published, Open Me...I'thou a Domestic dog, with a narrator who tries to convince its readers that information technology is a canis familiaris via pop-ups and an attached leash.[69] From 2000 to 2003, Spiegelman and Mouly edited three issues of the children's comics anthology Little Lit, with contributions from Raw alumni and children'due south book authors and illustrators.[seventy]

Postal service-September 11 (2001–nowadays) [edit]

Spiegelman lived close to the World Merchandise Middle site, which was known equally "Ground Zero" after the September 11 attacks that destroyed the Earth Trade Center.[71] Immediately following the attacks Spiegelman and Mouly rushed to their daughter Nadja's school, where Spiegelman's anxiety served but to increase his daughter's apprehensiveness over the situation.[61] Spiegelman and Mouly created a embrace for the September 24 result of The New Yorker [72] [73] which at first glance appears to be totally black, but upon close examination it reveals the silhouettes of the World Trade Centre towers in a slightly darker shade of black. Mouly positioned the silhouettes so that the North Tower'southward antenna breaks into the "w" of The New Yorker 's logo. The towers were printed in black on a slightly darker black field employing standard 4-color printing inks with an overprinted articulate varnish. In some situations, the ghost images only became visible when the magazine was tilted toward a light source.[72] Spiegelman was critical of the Bush administration and the mass media over their treatment of the September 11 attacks.[74]

Spiegelman did not renew his New Yorker contract after 2003.[75] He afterward quipped that he regretted leaving when he did, as he could take left in protest when the magazine ran a pro-invasion of Republic of iraq piece later in the year.[76] Spiegelman said his parting from The New Yorker was part of his general thwarting with "the widespread conformism of the mass media in the Bush era".[77] He said he felt like he was in "internal exile"[74] following the September xi attacks as the U.Due south. media had become "bourgeois and timid"[74] and did not welcome the provocative art that he felt the need to create.[74] All the same, Spiegelman asserted he left non over political differences, as had been widely reported,[75] only because The New Yorker was not interested in doing serialized work,[75] which he wanted to practise with his next project.[76]

Spiegelman responded to the September 11 attacks with In the Shadow of No Towers, commissioned by German newspaper Die Zeit, where it appeared throughout 2003. The Jewish Daily Forward was the only American periodical to serialize the feature.[74] The collected work appeared in September 2004 as an oversized[a] lath volume of two-page spreads which had to be turned on end to read.[78]

In the June 2006 edition of Harper's Mag Spiegelman had an article published on the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy; some interpretations of Islamic constabulary prohibit the depiction of Muhammad. The Canadian chain of booksellers Indigo refused to sell the effect. Called "Drawing Blood: Outrageous Cartoons and the Art of Outrage", the article surveyed the sometimes dire effect political cartooning has for its creators, ranging from Honoré Daumier, who spent time in prison for his satirical work; to George Grosz, who faced exile. To Indigo the article seemed to promote the continuance of racial extravaganza. An internal memo brash Indigo staff to tell people: "the decision was fabricated based on the fact that the content about to be published has been known to ignite demonstrations around the world."[79] In response to the cartoons, Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad promoted an Iranian cartoon contest seeking anti-Semitic cartoons. The organizers of the contest intended to highlight what they perceived as Western double standards surrounding anti-Semitism and Islamophobia. Spiegelman produced a drawing of a line of prisoners being led to the gas chambers; i stops to look at the corpses around him and says, "Ha! Ha! Ha! What's really hilarious is that none of this is really happening!"[eighty]

To promote literacy in young children, Mouly encouraged publishers to publish comics for children.[81] Disappointed by publishers' lack of response, from 2008 she self-published a line of easy readers called Toon Books, past artists such as Spiegelman, Renée French, and Rutu Modan, and promotes the books to teachers and librarians for their educational value.[82] Spiegelman's Jack and the Box was one of the inaugural books in 2008.[83]

In 2008 Spiegelman reissued Breakdowns in an expanded edition including "Portrait of the Artist every bit a Young %@&*!"[84] an autobiographical strip that had been serialized in the Virginia Quarterly Review from 2005.[85] A volume fatigued from Spiegelman's sketchbooks, Be A Nose, appeared in 2009. In 2011, MetaMaus followed—a book-length analysis of Maus by Spiegelman and Hillary Chute with a DVD update of the earlier CD-ROM.[86]

Library of America commissioned Spiegelman to edit the two-volume Lynd Ward: Half-dozen Novels in Woodcuts, which appeared in 2010, collecting all of Ward'south wordless novels with an introduction and annotations by Spiegelman. The project led to a touring testify in 2014 about wordless novels chosen Wordless! with live music by saxophonist Phillip Johnston.[87] Fine art Spiegelman's Co-Mix: A Retrospective débuted at Angoulême in 2012 and past the end of 2014 had traveled to Paris, Cologne, Vancouver, New York, and Toronto.[84] The book Co-Mix: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics, and Scraps, which complemented the show, appeared in 2013.[88]

In 2015, after vi writers refused to sit on a console at the PEN American Center in protest of the planned "freedom of expression courage award" for the satirical French journal Charlie Hebdo post-obit the shooting at its headquarters earlier in the yr, Spiegelman agreed to be ane of the replacement hosts,[89] forth with other names in comics such as writer Neil Gaiman. Spiegelman retracted a cover he had submitted to a Gaiman-edited "proverb the unsayable" effect of New Statesman when the management declined to impress a strip of Spiegelman'south. The strip, "Notes from a Commencement Amendment Fundamentalist", depicts Muhammad, and Spiegelman believed the rejection was censorship, though the mag asserted it never intended to run the cartoon.[xc]

In 2021, Literary Hub announced that Spiegelman was co-creating a work Street Cop with author Robert Coover.[91]

Personal life [edit]

Spiegelman married Françoise Mouly on July 12, 1977,[92] in a New York city hall anniversary.[39] They remarried subsequently in the year after Mouly converted to Judaism to delight Spiegelman'southward father.[39] Mouly and Spiegelman have two children together: a daughter, Nadja Rachel, born in 1987,[92] and a son, Dashiell Alan, born in 1992.[92]

Manner [edit]

"All comic-strip drawings must function every bit diagrams, simplified moving picture-words that indicate more they show."

—Art Spiegelman[93]

Spiegelman suffers from a lazy eye, and thus lacks depth perception. He says his art manner is "really a result of [his] deficiencies". His is a manner of labored simplicity, with dense visual motifs which ofttimes go unnoticed upon outset viewing.[94] He sees comics every bit "very condensed thought structures", more alike to poesy than prose, which need careful, fourth dimension-consuming planning that their seeming simplicity belies.[95] Spiegelman's work prominently displays his business organisation with form, and pushing the boundaries of what is and is non comics. Early on in the underground comix era, Spiegelman proclaimed to Robert Crumb, "Fourth dimension is an illusion that can be shattered in comics! Showing the aforementioned scene from unlike angles freezes it in time past turning the page into a diagram—an orthographic projection!"[96] His comics experiment with time, space, recursion, and representation. He uses the word "decode" to express the action of reading comics[97] and sees comics as performance best when expressed as diagrams, icons, or symbols.[93]

Spiegelman has stated he does not run into himself primarily as a visual artist, ane who instinctively sketches or doodles. He has said he approaches his work as a writer equally he lacks confidence in his graphic skills. He subjects his dialogue and visuals to constant revision—he reworked some dialogue balloons in Maus upwardly to forty times.[98] A critic in The New Republic compared Spiegelman's dialogue writing to a young Philip Roth in his ability "to make the Jewish voice communication of several generations audio fresh and disarming".[98]

Spiegelman makes utilize of both old- and new-fashioned tools in his work. He prefers at times to piece of work on paper on a drafting tabular array, while at others he draws straight onto his calculator using a digital pen and electronic drawing tablet, or mixes methods, employing scanners and printers.[95]

Influences [edit]

Harvey Kurtzman has been Spiegelman's strongest influence as a cartoonist, editor, and promoter of new talent.[99] Master among his other early cartooning influences include Will Eisner,[100] John Stanley'southward version of Little Lulu, Winsor McCay'southward Little Nemo, George Herriman's Krazy Kat,[99] and Bernard Krigstein's short strip "Primary Race".[101]

In the 1960s Spiegelman read in comics fanzines about graphic artists such as Frans Masereel, who had fabricated wordless novels in woodcut. The discussions in those fanzines about making the Great American Novel in comics subsequently acted as inspiration for him.[46] Justin Greenish's comic book Binky Dark-brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary (1972) motivated Spiegelman to open up upwardly and include autobiographical elements in his comics.[102]

Spiegelman acknowledges Franz Kafka every bit an early influence,[103] whom he says he has read since the age of 12,[104] and lists Vladimir Nabokov, William Faulkner, Gertrude Stein amid the writers whose work "stayed with" him.[105] He cites non-narrative avant-garde filmmakers from whom he has drawn heavily, including Ken Jacobs, Stan Brakhage, and Ernie Gehr, and other filmmakers such equally Charlie Chaplin and the makers of The Twilight Zone.[106]

Beliefs [edit]

Spiegelman is a prominent advocate for the comics medium and comics literacy. He believes the medium echoes the manner the human brain processes information. He has toured the U.Due south. with a lecture called "Comix 101", examining its history and cultural importance.[107] He sees comics' low status in the late 20th century as having come down from where information technology was in the 1930s and 1940s, when comics "tended to appeal to an older audience of GIs and other adults".[108] Following the appearance of the censorious Comics Code Authority in the mid-1950s, Spiegelman sees comics' potential as having stagnated until the rise of underground comix in the tardily 1960s.[108] He taught courses in the history and aesthetics of comics at schools such as the School of Visual Arts in New York.[35] Every bit co-editor of Raw, he helped propel the careers of younger cartoonists whom he mentored, such as Chris Ware,[76] and published the work of his School of Visual Arts students, such every bit Kaz, Drew Friedman, and Mark Newgarden. Some of the work published in Raw was originally turned in as course assignments.[53]

Spiegelman has described himself politically every bit "firmly on the left side of the secular-fundamentalist split up" and a "1st Amendment absolutist".[80] As a supporter of free spoken communication, Spiegelman is opposed to hate speech laws. He wrote a critique in Harper'due south on the controversial Muhammad cartoons in the Jyllands-Posten in 2006; the issue was banned from Indigo–Chapters stores in Canada. Spiegelman criticized American media for refusing to reprint the cartoons they reported on at the fourth dimension of the Charlie Hebdo shooting in 2015.[109]

Spiegelman is a non-practicing Jew and considers himself "a-Zionist"—neither pro- nor anti-Zionist; he has called Israel "a distressing, failed idea".[75] He told Peanuts creator Charles Schulz he was not religious, merely identified with the "alienated diaspora culture of Kafka and Freud ... what Stalin pejoratively called rootless cosmopolitanism".[110]

Legacy [edit]

Maus looms large not but over Spiegelman'south trunk of work, only over the comics medium itself. While Spiegelman was far from the first to do autobiography in comics, critics such equally James Campbell considered Maus the work that popularized information technology.[eleven] The bestseller has been widely written nearly in the popular press and academia—the quantity of its critical literature far outstrips that of any other work of comics.[111] Information technology has been examined from a bang-up variety of academic viewpoints, though most often by those with little understanding of Maus ' context in the history of comics. While Maus has been credited with lifting comics from popular civilization into the earth of loftier art in the public imagination, criticism has tended to ignore its deep roots in popular civilization, roots that Spiegelman has intimate familiarity with and has devoted considerable time to promote.[112]

Spiegelman's belief that comics are best expressed in a diagrammatic or iconic fashion has had a particular influence on formalists such as Chris Ware and his old student Scott McCloud.[93] In 2005, the September 11-themed New Yorker encompass placed 6th on the top ten of mag covers of the previous 40 years by the American Lodge of Magazine Editors.[72] Spiegelman has inspired numerous cartoonists to accept up the graphic novel as a means of expression, including Marjane Satrapi.[99]

A articulation ZDF–BBC documentary, Art Spiegelman's Maus, was televised in 1987.[113] Spiegelman, Mouly, and many of the Raw artists appeared in the documentary Comic Book Confidential in 1988.[54] Spiegelman's comics career was likewise covered in an Emmy-nominated PBS documentary, Serious Comics: Art Spiegelman, produced by Patricia Zur for WNYC-Tv in 1994. Spiegelman played himself in the 2007 episode "Husbands and Knives" of the animated television series The Simpsons with fellow comics creators Daniel Clowes and Alan Moore.[114] A European documentary, Fine art Spiegelman, Traits de Mémoire, appeared in 2010 and afterwards in English nether the championship The Art of Spiegelman,[113] directed by Clara Kuperberg and Joelle Oosterlinck and mainly featuring interviews with Spiegelman and those around him.[115]

Awards [edit]

- 1982: Playboy Editorial Award, Best Comic Strip[116]

- 1982: Yellowish Kid Award, Lucca, Italian republic, for Strange Author[117] [116]

- 1983: Impress, Regional Design Award[116]

- 1984: Print, Regional Pattern Accolade[116]

- 1985: Print, Regional Design Award[116]

- 1986: Joel M. Cavior, Jewish Writing[118]

- 1987: Inkpot Award[116]

- 1988: Angoulême International Comics Festival, France, Prize for Best Comic Book, for Maus [54]

- 1988: Urhunden Prize, Sweden, Best Foreign Album, for Maus [119]

- 1990: Guggenheim Fellowship.[54]

- 1990: Max & Moritz Prize, Erlangen, Germany, Special Prize, for Maus [118]

- 1992: Pulitzer Prize Letters award, for Maus [120]

- 1992: Eisner Award, Best Graphic Album (reprint), for Maus [121]

- 1992: Harvey Award, All-time Graphic Album of Previously Published Work, for Maus [122]

- 1992: Los Angeles Times, Volume Prize for Fiction for Maus II [123]

- 1993: Angoulême International Comics Festival, Prize for Best Comic Book, for Maus II [54]

- 1993: Sproing Award, Norway, Best Foreign Album, for Maus [118]

- 1993: Urhunden Prize, All-time Foreign Album, for Maus II [119]

- 1995: Binghamton University (formerly Harpur Higher), honorary Doctorate of Letters.[66]

- 1999: Eisner Award, inducted into the Hall of Fame[65]

- 2005: French government, Chevalier of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres[65]

- 2005: Time magazine, i of the "Top 100 Almost Influential People"[124]

- 2011: Angoulême International Comics Festival, Grand Prix[125]

- 2011: National Jewish Volume Award for MetaMaus: A Look Inside a Modern Classic, Maus[126]

- 2015: American University of Arts and Messages membership[127]

- 2018: The Edward MacDowell Medal

Bibliography [edit]

[edit]

- Tijuana Bibles: Art and Wit in America'due south Forbidden Funnies, 1930s-1950s (Introductory Essay: Those Dirty Fiddling Comics) (1977)

- Breakdowns: From Maus to Now, an Anthology of Strips (1977)

- Maus (1991)

- The Wild Party (1994)

- Open up Me, I'm A Dog (1995)

- Jack Cole and Plastic Man: Forms Stretched to Their Limits (2001)

- In the Shadow of No Towers (2004)

- Breakdowns: Portrait of the Creative person equally a Young %@&*! (2008)

- Jack and the Box (2008)

- Exist a Nose (2009)

- MetaMaus (2011)

- Co-Mix: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics, and Scraps (2013)

- Street Cop (with Robert Coover) (2021)

Editor [edit]

- Short Club Comix (1972–74)

- Whole Grains: A Book of Quotations (with Bob Schneider, 1973)

- Arcade (with Bill Griffith, 1975–76)

- Raw (with Françoise Mouly, 1980–91)

- Metropolis of Glass (graphic novel accommodation by David Mazzucchelli of the Paul Auster novel, 1994)

- The Narrative Corpse (1995)

- Little Lit (with Françoise Mouly, 2000–2003)

- The TOON Treasury of Archetype Children's Comics (with Françoise Mouly, 2009)

- Lynd Ward: Six Novels in Woodcuts (2010)

Notes [edit]

- ^ The volume edition of In the Shadow of No Towers measures 10 in × 14.5 in (25 cm × 37 cm).[78]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d Spiegelman 2011, p. 18.

- ^ Naughtie 2012.

- ^ Spiegelman 2011, p. 16.

- ^ Teicholz 2008.

- ^ Hatfield 2005, p. 146.

- ^ Hirsch 2011, p. 37.

- ^ a b Kois 2011.

- ^ a b c Witek 2007b, p. xvii.

- ^ a b Horowitz 1997, p. 401.

- ^ Gardner 2017, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b c Campbell 2008, p. 56.

- ^ Horowitz 1997; D'Arcy 2011.

- ^ Witek 2007b, pp. xvii–xviii.

- ^ Jamieson 2010, p. 116.

- ^ a b c d e f g Witek 2007b, pp. xviii.

- ^ a b Kaplan 2006, p. 102; Campbell 2008, p. 56.

- ^ Fathers 2007, p. 122; Gordon 2004; Horowitz 1997, p. 401.

- ^ a b Horowitz 1997, p. 402.

- ^ a b Kaplan 2006, p. 103.

- ^ Epel 2007, p. 144.

- ^ a b Witek 1989, p. 103.

- ^ Kaplan 2008, p. 140.

- ^ Conan 2011.

- ^ Short Order Comix #1 entry, Grand Comics Database. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ Fox, M. Steven. Curt Order Comix #one, Underground ComixJoint. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ Witek 1989, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Chute 2012, p. 413.

- ^ Donahue, Don and Susan Goodrick, editors. The Apex Treasury of Underground Comics (Links Books/Quick Fox, 1974).

- ^ Hatfield 2012, p. 138.

- ^ Hatfield 2012, p. 138; Chute 2012, p. 413.

- ^ Kuskin 2010, p. 68.

- ^ Rothberg 2000, p. 214; Witek 2007b, p. xviii.

- ^ Grishakova & Ryan 2010, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Buhle 2004, p. 252.

- ^ a b c d Witek 2007b, p. xix.

- ^ a b Kaplan 2006, p. 108.

- ^ Heer 2013, pp. 26–30.

- ^ Heller 2004, p. 137.

- ^ a b c Heer 2013, p. 41.

- ^ Heer 2013, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b Heer 2013, pp. 45–47.

- ^ Heer 2013, p. 49.

- ^ Kaplan 2006, pp. 111–112.

- ^ a b c Kaplan 2006, p. 109.

- ^ Reid 2007, p. 225.

- ^ a b Kaplan 2008, p. 171.

- ^ Fathers 2007, p. 125.

- ^ Blau 2008.

- ^ a b Kaplan 2006, p. 113.

- ^ Kaplan 2006, p. 118; Kaplan 2008, p. 172.

- ^ Kaplan 2008, p. 171; Kaplan 2006, p. 118.

- ^ Kaplan 2006, p. 115.

- ^ a b Kaplan 2006, p. 111.

- ^ a b c d e f m h Witek 2007b, p. 20.

- ^ Bellomo 2010, p. 154.

- ^ Witek 2007a.

- ^ Shandler 2014, p. 338.

- ^ Liss 1998, p. 54; Fischer & Fischer 2002; Pulitzer Prizes staff.

- ^ Campbell 2008, p. 59.

- ^ Mendelsohn 2003, p. 180; Campbell 2008, p. 59; Witek 2007b, p. xx.

- ^ a b Kaplan 2006, p. 119.

- ^ Fox 2012.

- ^ Spiegelman, Art; Sendak, Maurice (September 27, 1993). "In the Dumps". The New Yorker.

- ^ Weiss 2012; Witek 2007b, pp. twenty–xxi.

- ^ a b c d Witek 2007b, p. xxii.

- ^ a b c Witek 2007b, p. xxi.

- ^ a b Campbell 2008, p. 58.

- ^ a b Arnold 2001.

- ^ Publishers Weekly staff 1995.

- ^ Witek 2007b, pp. xxii–xxiii.

- ^ Baskind & Omer-Sherman 2010, p. xxi.

- ^ a b c ASME staff 2005.

- ^ "9/11 Magazine Covers > The New Yorker", ASME/magazine.org. Retrieved 2016-08-thirteen.

- ^ a b c d e Corriere della Sera staff 2003, p. 264.

- ^ a b c d Hays 2011.

- ^ a b c Campbell 2008, p. 60.

- ^ Corriere della Sera staff 2003, p. 263.

- ^ a b Chute 2012, p. 414.

- ^ Adams 2006.

- ^ a b Brean 2008.

- ^ Heer 2013, p. 115.

- ^ Heer 2013, p. 116.

- ^ Publishers Weekly staff 2008.

- ^ a b Solomon 2014, p. ane.

- ^ Witek 2007b, p. xxiii.

- ^ Heater 2011.

- ^ Artsy 2014.

- ^ Randle 2013.

- ^ Chow 2015.

- ^ Krayewski 2015; Heer 2015.

- ^ Temple, Emily (March nine, 2021). "Fine art Spiegelman and Robert Coover have collaborated (over Zoom!) on a new illustrated dystopian story". lithub.com. Literary Hub. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c Meyers 2011.

- ^ a b c Cates 2010, p. 96.

- ^ Campbell 2008, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b Campbell 2008, p. 61.

- ^ Chute 2012, p. 412.

- ^ Chute 2012, pp. 412–413.

- ^ a b Campbell 2008, p. 57.

- ^ a b c Zuk 2013, p. 700.

- ^ Frahm 2004.

- ^ Kannenberg 2001, p. 28.

- ^ Chute 2010, p. eighteen.

- ^ Mulman 2010, p. 86.

- ^ Kannenberg 2007, p. 262.

- ^ Horowitz 1997, p. 404.

- ^ Zuk 2013, pp. 699–700.

- ^ Kaplan 2006, p. 123.

- ^ a b Campbell 2008, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Brean 2015.

- ^ Mendelsohn 2003, p. 180.

- ^ Loman 2010, p. 217.

- ^ Loman 2010, p. 212.

- ^ a b Shandler 2014, p. 318.

- ^ Keller 2007.

- ^ Kensky 2012.

- ^ a b c d east f Brennan & Clarage 1999, p. 575.

- ^ Traini 1982.

- ^ a b c Zuk 2013, p. 699.

- ^ a b Hammarlund 2007.

- ^ Pulitzer Prizes staff.

- ^ Eisner Awards staff 2012.

- ^ Harvey Awards staff 1992.

- ^ Colbert 1992.

- ^ Time staff 2005; Witek 2007b, p. xxiii.

- ^ Cavna 2011.

- ^ "National Jewish Book Award | Book awards | LibraryThing". www.librarything.com . Retrieved 2020-01-18 .

- ^ Artforum staff 2015.

Works cited [edit]

- Adams, James (2006-05-27). "Indigo pulls controversial Harper'due south off the shelves". The World and Mail. Archived from the original on 2009-02-06.

- Arnold, Andrew D. (2001-09-07). "Lemons into Lemonade". Time . Retrieved 2015-01-xix .

- Artforum staff (2015-02-25). "Art Spiegelman Named Member of American Academy of Arts and Messages". Artforum . Retrieved 2015-05-04 .

- Artsy, Avishay (2014-10-07). "Cartoonist Art Spiegelman reveals his influences in 'Wordless!'". The Jewish Periodical of Greater Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 2014-10-23. Retrieved 2015-05-04 .

- ASME staff (2005-10-17). "ASME's Tiptop xl Magazine Covers of the Last forty Years". American Society of Mag Editors. Archived from the original on 2011-02-sixteen. Retrieved 2012-06-eleven .

- Baskind, Samantha; Omer-Sherman, Ranen (2010). The Jewish Graphic Novel: Critical Approaches. Rutgers University Press. ISBN978-0-8135-4775-half-dozen.

- Bellomo, Mark (2010). Totally Tubular '80s Toys. Krause Publications. ISBN978-1-4402-1647-3.

- Blau, Rosie (2008-eleven-29). "Breakfast with the FT: Fine art Spiegelman". Financial Times . Retrieved 2012-04-18 .

- Brean, Joseph (2008-04-01). "Fine art Spiegelman: Politically right 'fever' grips Canada". National Mail service . Retrieved 2015-05-04 .

- Brean, Joseph (2015-01-30). "Marking Steyn on swain free-speech advocate Art Spiegelman and what information technology means to exist truly provocative". National Mail service . Retrieved 2015-05-04 .

- Brennan, Elizabeth A.; Clarage, Elizabeth C. (1999). "Art Spiegelman". Who'due south Who of Pulitzer Prize Winners. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 574–575. ISBN978-i-57356-111-2.

- Buhle, Paul (2004). From the Lower Eastward Side to Hollywood: Jews in American Popular Civilization . Verso. ISBN978-1-85984-598-one.

- Campbell, James (2008). Syncopations: Beats, New Yorkers, and Writers in the Dark . University of California Press. ISBN978-0-520-25237-0.

- Cates, Isaac (2010). "Comics and the Grammer of Diagrams". In Brawl, David M.; Kuhlman, Martha B. (eds.). The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing Is a Way of Thinking. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 90–105. ISBN978-ane-60473-442-3.

- Cavna, Michael (February ane, 2011). "'Maus' creator reacts to winning comics' Grand Prix prize". The Washington Post . Retrieved Jan 19, 2015.

- Grub, Andrew R. (2015-05-03). "After Protest Over Accolade, Neil Gaiman and Art Spiegelman Agree to Exist Table Hosts at PEN Gala". The New York Times . Retrieved 2015-03-04 .

- Chute, Hillary L. (2010). Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics. Columbia University Printing. ISBN978-0-231-15062-0.

- Chute, Hillary 50. (2012). "Graphic Narrative". In Bray, Joe; Gibbons, Alison; McHale, Brian (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Experimental Literature. Routledge. pp. 407–419. ISBN978-0-415-57000-8.

- Colbert, James (1992-eleven-08). "Times Book Prizes 1992: Fiction: On Maus II". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved 2012-01-31 .

- Conan, Neal (2011-ten-05). "'MetaMaus': The Story Behind Spiegelman's Classic". NPR . Retrieved 2012-05-08 .

- Corriere della Sera staff (2007) [2003]. "Art Spiegelman, Cartoonist for the New Yorker, Resigns in Protest at Censorship". In Witek, Joseph (ed.). Art Spiegelman: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 263–266. ISBN978-i-934110-12-half dozen.

- D'Arcy, David (2011-07-thirteen). "Art Goes Dorsum to School". The Art Newspaper . Retrieved 2012-06-11 .

- Eisner Awards staff (2012). "Complete List of Eisner Laurels Winners". San Diego Comic-Con International. Archived from the original on 2011-04-27. Retrieved 2012-01-31 .

- Epel, Naomi (2007). "Fine art Spiegelman". In Witek, Joseph (ed.). Art Spiegelman: Conversations. University Printing of Mississippi. pp. 143–151. ISBN978-i-934110-12-6.

- Fathers, Michael (2007). "Fine art Mimics Life in the Death Camps". In Witek, Joseph (ed.). Art Spiegelman: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 122–125. ISBN978-i-934110-12-6.

- Fischer, Heinz Dietrich; Fischer, Erika J. (2002). "Spiegelman, Art". Complete Biographical Encyclopedia of Pulitzer Prize Winners, 1917–2000: Journalists, Writers and Composers on Their Means to the Coveted Awards. Walter de Gruyter. p. 230. ISBN978-three-598-30186-five.

- Fox, Killian (2012-04-29). "The Covers the New Yorker Rejected". The Observer . Retrieved 2012-12-05 .

- Frahm, Ole (May 2004). "Considering MAUS. Approaches to Art Spiegelman'southward "Survivor'due south Tale" of the Holocaust past Deborah R. Geis (ed.)". Image & Narrative (8). ISSN 1780-678X. Retrieved 2012-01-30 .

- Gardner, Jared (Spring 2017). "Earlier the Hole-and-corner: Jay Lynch, Art Spiegelman, Skip Williamson and the Fanzine Culture of the Early on 1960s". Inks: The Periodical of the Comics Studies Social club. The Ohio State University Press. 1 (1): 75–99. doi:10.1353/ink.2017.0005. S2CID 194727887 – via Project MUSE.

- Gordon, Andrew (2004). "Jewish Fathers and Sons in Spiegelman's Maus and Roth'southward Patrimony". ImageTexT. ane (ane). Archived from the original on 2005-12-31.

- Grishakova, Marina; Ryan, Marie-Laure (2010). Intermediality and Storytelling. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN978-3-11-023774-0.

- Hammarlund, Ola (2007-08-08). "Urhunden: Satir och iransk kvinnoskildring får seriepris" (in Swedish). Urhunden. Archived from the original on 2019-04-13. Retrieved 2012-04-27 .

- Harvey Awards staff (1992). "1992 Harvey Accolade Winners". Harvey Awards. Archived from the original on 2016-03-15. Retrieved 2012-01-31 .

- Hatfield, Charles (2012). "An Art of Tensions". In Heer, Jeet; Worcester, Kent (eds.). A Comics Studies Reader. Academy Press of Mississippi. pp. 132–148. ISBN978-1-60473-109-v.

- Hatfield, Charles (2005). Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN978-ane-57806-719-0.

- Hays, Matthew (2011-ten-08). "Of Maus and Man: Art Spiegelman Revisits his Holocaust Classic". The Globe and Post. Archived from the original on 2015-01-19. Retrieved 2012-12-03 .

- Heater, Brian (October eleven, 2011). "Art Spiegelman On The Future of the Volume". Publishers Weekly . Retrieved January xix, 2015.

- Heer, Jeet (2013). In Love with Art: Françoise Mouly'southward Adventures in Comics with Art Spiegelman. Coach House Books. ISBN978-1-77056-351-3.

- Heer, Jeet (2015-06-09). "The Controversy Over Muhammad Cartoons Is Not About the Prophet Muhammad". Archived from the original on 2015-06-ten. Retrieved 2015-08-sixteen .

- Heller, Steven (2004). Blueprint Literacy: Agreement Graphic Design. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. ISBN978-1-58115-356-ix.

- Hirsch, Marianne (2011). "Mourning and Postmemory". In Chaney, Michael A. (ed.). Graphic Subjects: Critical Essays on Autobiography and Graphic Novels . University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 17–44. ISBN978-0-299-25104-8.

- Horowitz, Sara R. (1997). "Art Spiegelman". In Shatzky, Joel; Taub, Michael (eds.). Contemporary Jewish-American Novelists: A Bio-Critical Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 400–408. ISBN978-0-313-29462-four.

- Jamieson, Dave (2010). Mint Condition: How Baseball Cards Became an American Obsession. Atlantic Monthly Printing. ISBN978-0-8021-1939-1.

- Kannenberg, Gene, Jr. (2001). "'I Looked Just Like Rudolph Valentino': Identity and Representation in Maus". In Baetens, Jan (ed.). The Graphic Novel. Leuven University Printing. pp. 79–89. ISBN978-ninety-5867-109-7.

- Kannenberg, Gene, Jr. (2007). "A Conversation with Art Spiegelman". In Witek, Joseph (ed.). Fine art Spiegelman: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 238–262. ISBN978-1-934110-12-6.

- Kaplan, Arie (2006). "Art Spiegelman". Masters of the Comic Book Universe Revealed!. Chicago Review Press. pp. 99–124. ISBN978-one-55652-633-half dozen.

- Kaplan, Arie (2008). From Krakow to Krypton: Jews and Comic Books. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN978-0-8276-0843-6.

- Keller, Richard (2007-11-18). "The Simpsons: Husbands and Knives". The Huffington Postal service . Retrieved 2014-10-fourteen .

- Kensky, Eitan (2012-11-08). "Art Spiegelman Struggles With Success". The Forward. Archived from the original on 2015-08-17. Retrieved 2015-08-17 .

- Kois, Dan (2011-12-02). "The Making of 'Maus'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2011-12-05. Retrieved 2012-01-27 .

- Krayewski, Ed (2015-06-03). "Art Spiegelman Pulls New Statesman Cover Because It Wouldn't Print a Cartoon Featuring Mohammed: 'Death by a thousand buts'". Reason. Archived from the original on 2015-06-06. Retrieved 2015-08-16 .

- Kuskin, William (2010). "Vulgar Metaphysicians: William S. Burroughs, Alan Moore, Art Spiegelman, and the Medium of the Book". In Grishakova, Marina; Ryan, Marie-Laure (eds.). Intermediality and Storytelling. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 49–77. ISBN978-3-eleven-023773-3.

- Liss, Andrea (1998). Trespassing Through Shadows: Retention, Photography, and the Holocaust. Academy of Minnesota Press. ISBN978-0-8166-3060-8.

- Loman, Andrew (2010). ""That Mouse'due south Shadow": The Canonization of Spiegelman's Maus". In Williams, Paul; Lyons, James (eds.). The Rise of the American Comics Artist: Creators and Contexts. Academy Printing of Mississippi. pp. 210–235. ISBN978-ane-60473-792-9 . Retrieved 2012-06-eleven .

- Mendelsohn, Ezra (2003). "Jewish Universalism: Some Visual Texts and Subtexts". In Kugelmass, Jack (ed.). Central Texts in American Jewish Civilization. Rutgers University Press. pp. 163–184. ISBN978-0-8135-3221-ix.

- Meyers, Julia M. (2011). "Smashing Lives from History: Jewish Americans : Art Spiegelman". Salem Printing. Archived from the original on 2011-08-20. Retrieved 2012-04-18 .

- Mulman, Lisa Naomi (2010). "A Tale of 2 Mice: Graphic Representations of the Jew in Holocaust Narrative". In Baskind, Samantha; Omer-Sherman, Ranen (eds.). The Jewish Graphic Novel: Critical Approaches. Rutgers University Press. pp. 85–93. ISBN978-0-8135-4775-6 . Retrieved 2012-06-11 .

- Naughtie, James (2012-02-05). "Art Spiegelman". Bookclub. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 2014-01-18 .

- Publishers Weekly staff (1995). "Children'southward Volume Review: Open up Me...I'k a Domestic dog! by Fine art Spiegelman". Publishers Weekly . Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- Publishers Weekly staff (2008). "Children's Volume Review: Jack and the Box by Art Spiegelman". Publishers Weekly . Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- Pulitzer Prizes staff. "Special Awards and Citations". The Pulitzer Prizes . Retrieved 2013-11-02 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Randle, Chris (2013-09-27). "Volume Review: Co-Mix, past Art Spiegelman". National Post . Retrieved 2015-05-04 .

- Reid, Calvin (2007). "Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly: The Literature of Comics". In Witek, Joseph (ed.). Art Spiegelman: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 223–229. ISBN978-1-934110-12-half-dozen.

- Rothberg, Michael (2000). Traumatic Realism: The Demands of Holocaust Representation. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN978-0-8166-3459-0.

- Shandler, Jeffrey (2014). "Art Spiegelman: The Complete Maus". In Rebhun, Uzi (ed.). The Social Scientific Written report of Jewry: Sources, Approaches, Debates. Oxford University Press. pp. 337–341. ISBN978-0-19-936349-0.

- Smith, Graham (2007) [1987]. "From Mickey to Maus: Recalling the Genocide Through Cartoon". In Witek, Joseph (ed.). Fine art Spiegelman: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 84–94. ISBN978-1-934110-12-6. (Originally in Oral History Journal Vol. 15, Spring 1987)

- Solomon, Alisa (2014-08-27). "The Haus of Maus: Art Spiegelman'southward twitchy blasphemy". The Nation. Archived from the original on 2015-02-xx. Retrieved 2015-05-04 .

- Spiegelman, Fine art (2011). Chute, Hillary (ed.). MetaMAUS. Viking Press. ISBN978-0-670-91683-2.

- Teicholz, Tom (2008-12-25). "The 'Maus' that Roared". JewishJournal.com . Retrieved 2012-12-06 .

- Time staff (2005-04-xviii). "Art Spiegelman - The 2005 Time 100". Time. Archived from the original on June xviii, 2010. Retrieved 2012-06-11 .

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Traini, Rinaldo (1982). "15° SALONE, 1982" (in Italian). Immagine-Centro Studi Iconografici. Archived from the original on 2011-02-27.

- Weiss, Sasha (2012-05-09). "Fine art Spiegelman Discusses Maurice Sendak". The New Yorker . Retrieved 2012-12-05 .

- Witek, Joseph (1989). Comic Books as History: The Narrative Art of Jack Jackson, Art Spiegelman, and Harvey Pekar. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN978-0-87805-406-0.

- Witek, Joseph, ed. (2007). "Introduction". Art Spiegelman: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. pp. nine–16. ISBN978-i-934110-12-6.

- Witek, Joseph, ed. (2007). "Chronology". Art Spiegelman: Conversations. University Printing of Mississippi. pp. xvii–xiii. ISBN978-1-934110-12-6.

- Zuk, Tanya Z. (2013). Duncan, Randy; Smith, Matthew J. (eds.). Icons of the American Comic Volume: From Captain America to Wonder Adult female. ABC-CLIO. pp. 697–707. ISBN978-0-313-39923-7.

Further reading [edit]

- The Topps Company Inc. (2008). Wacky Packages. Harry Northward. Abrams. ISBN978-0-8109-9531-iv.

- The Topps Company Inc. (2012). Garbage Pail Kids. Harry Due north. Abrams. ISBN978-1-4197-0270-9.

External links [edit]

- Appearances on C-Span

- Lambiek Comiclopedia article.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_Spiegelman

0 Response to "Why Did Art Spiegalman Go to a Mental Hosepital"

Post a Comment